In the fall of 1870, nearly 800 residents in the Butler County area formed a vigilance committee to address widespread livestock theft. By mid-December, they had executed eight men of questionable guilt. The sheriff issued warrants for the arrest of 89 of the vigilantes, yet local law enforcement proved unsuccessful in containing their armed resistance. The confrontation ended when the adjutant general and an attorney representing the vigilantes negotiated a resolution. The vigilantes claimed that incompetence and corruption within the legal system made it necessary for them to employ extralegal means to remove this threat to their lives and property. The evidence, however, does not fully support their argument. Despite their size, and the number of victims, the Butler County vigilantes have received little scholarly attention. This study provides an in-depth examination of the episode.

Historical interpretations of western vigilantism do not fully address the complexities of the event. This project augments the historical examinations with theoretical approaches borrowed from the disciplines of philosophy, psychology, sociology, and anthropology to generate a more comprehensive interpretive model. This model is comprised of four components. 1) Context and Conduciveness: an overview of the regional history, legal traditions, and the history of their law enforcement system. 2) Mobilization: an examination of the manner in which community leaders shaped the discourse surrounding the events and the selection of a scapegoat or deviant group on whom they attached responsibility. 3) Action and Reaction: an examination of the written accounts of the lynchings, as well as the physical evidence. 4) Evaluation: an assessment of the residents’ perceptions and the evolution of a community myth defining the events. This approach offers a more comprehensive assessment of the intersection of contributory factors that led to vigilantism. It also provides a method for examining what these events meant to local residents, the manner in which the community survived this phase of its history, and how the residents reconstructed their community identity.

This project represents a long journey, the culmination of which was made possible only through the assistance and guidance of a number of people. I am indebted to Professors Rita Napier, Lloyd Sponholtz, Ray Hiner, Ted Wilson and Brian Donovan. Their patience, suggestions and unfailing support have been invaluable. I am deeply grateful to Ellen Garber for her encouragement and friendship, as well as to Sandee Kennedy for her support and assistance. These two strong women made it possible for me to overcome a number of obstacles to complete this project.

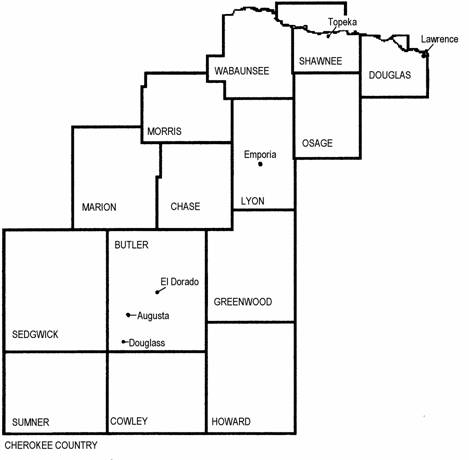

The archivists and historians of many libraries and historical societies have been extraordinarily helpful. These included the Douglass Historical Museum and the Douglass Public Library; the Winfield Public Library and the Cowley County Historical Society in Winfield; the Kansas Oil & Gas Museum, the Butler County Historical Society and the Butler County Courthouse in El Dorado; the Flint Hills Genealogical Society and the Lyon County Historical Society Archives in Emporia; the Kansas State Historical Society Archives in Topeka; and the Kansas Collection of the Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. I am particularly appreciative of the enthusiastic assistance I received from Professor Sam Dicks of Emporia State University; Linda Lavington and Bill Ikerd of the Lyon County Historical Society Archives; Frances Renfro of the Douglass Historical Society; Douglass historian J. Mark Alley; and Bill Bottorff, Mary Ann Wortman, Jerry Wallace, Debi Stokes and the other Cowley County local historians who generously shared their research. Dale Broadsword, Sandy Kirkhoven and Linda Chang contributed their family stories. Del Mar College faculty and staff were tremendously supportive of this project as well.

I would like to thank my husband Bryan and my children Michael and Amanda for their patience and willingness to explore dusty archives with me; and my parents Curry and Barbara Miles for their consistent support and enthusiastic assistance in the Douglass cemetery.

ABSTRACT

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

LIST OF MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

Chapter

1. Introduction to the “Butler County Trouble” 1

2. Understanding Vigilantism: A Collaborative Effort 14

3. Context and Conduciveness 86

4. Moblization 122

5. Action and Reaction 157

6. Evaluation 214

BIBLIOGRAPHY 251

Appendices

1. Alleged Horses Thieves Data 262

2. Vigilantes and Vigilante Supporters Data, Pt. 1 263

3. Vigilantes and Vigilante Supporters Data, Pt. 2 264

Figure Page

MAPS

1. Central Kansas, 1869 6

2. Butler County region, 1857 104

3. Butler County area, 1867 108

4. Central Kansas, 1869-1870 123

5. Townships along the border between

Butler County and Cowley County 130

6. Walnut and Douglass Townships, Butler County, 1870 158

7. Lynching Sites, Butler and Cowley Counties, 1870 179

LETTERS

1. Letter to Dr. McKinsey, Coroner, 3 December 1870 180

2. Letter to Adjutant General Whittaker, 8 December 1870 197

ILLUSTRATIONS

1. Wm T. Galliher, Advertisement, 1866 171

2. Democratic Convention, Advertisement, 1867 172

3. Dr. J. F. Morris, Advertisement, 1870 175

4. Wm. Quimby, Administrator Notice, 1870 177

5. Butler County Court House, 1867 & 1875 200

6. Murdock Signature 201

7. W. M. R. $25 Reward Notice, 1870 224

8. Martha Quimby, Administratrix Notice, 1870 224

9. Lynching Illustration, 1954 234

10. The West, Cover and Article, 1965 235

11. Douglass Lynching, Watercolor 245

In the years immediately following the Civil War, horse and cattle thieves plagued the plains of central Kansas. During 1870, the residents of Butler, Cowley and Sedgwick counties suffered the loss of more than three hundred horses. Local reports claimed that “in hardly any instance was a horse recovered, and no horse thief has been successfully prosecuted in any court of justice.”[2] While that statement is not completely truthful, it nevertheless reflected popular sentiment in the region.

The violence in Butler County escalated in the early fall of 1870, following the theft of several mules from a family of recent arrivals. The vigilance committee sought retribution late in the evening on Tuesday, November 8, 1870.

A crowd of approximately fourteen men arrived at the home of Lewis Booth, a long-time resident of the area. Booth lived just south of Douglass in Butler County. With pistols drawn the men entered his home. They demanded that Lewis Booth, his brother George, and their friend Jack Corbin, a government scout accompany them outside. The party of men accused these three of participating in a widespread horse and cattle theft operation. Lewis’ wife Jennie remained inside with their two daughters, while the vigilantes forced the three men outside.

The vigilantes escorted their captives to a sycamore tree approximately one hundred yards from the house and began preparations for hanging them. Jack Corbin was strung up first. In the last moments before he died, the vigilantes claimed Corbin made a confession to his executioners. He allegedly named fifty men who directed the horse theft operation in south-central Kansas. After he gave the names of his fellow horse-thieves, the vigilantes hanged him from the tree. While they were occupied with Corbin, the vigilantes later maintained, the Booth brothers seized the opportunity to attempt an escape. Turning their attention to the Booths, the vigilantes fired fifteen shots, followed by three more. Lewis Booth took one bullet to the head and another to the chest that left him powder-burned. Like his brother, George was fatally hit in the head and chest. Their task completed, the vigilantes left the scene. As they made their way back to town, they came across James Smith who was crossing Little Walnut Creek. The vigilantes later claimed that Smith was on his horse when he saw the group and opened fire. The men returned his fire, and brought Smith down, along with his horse. The men carried his body to the bank of the creek. They left it there with a placard reading “Shot for a horse thief.”[4]

The vigilance committee involved in these deaths was larger than the fourteen or so men that Jennie Booth reported coming into her home. Following the lynching, local authorities issued warrants for 87 men and one woman charging them with complicity in the executions.[5] Before they could serve all of the warrants, however, the vigilantes struck again.

The confession wrested from Corbin had ensured that the violence would continue. Less than a month after the first four alleged thieves had been killed, the party of vigilantes had grown to over one hundred citizens. Four more men soon fell victim to their summary judgment: William G. Quimby, owner of a general merchandise store; Michael Drea, Quimby’s clerk; Dr. James F. Morris, a physician and surgeon; and Alexander Morris, James’s son and owner of a drug store. Local newspaper accounts claimed that the latest victims were four of the more notorious of the thieves named in Corbin’s confession. They were arrested for purchasing stolen horses, and appeared before the county justice for a preliminary examination on November 28, 1870. These four were prominent businessmen and community leaders and were believed by the county attorneys to be important state’s witnesses against the vigilantes.

The four alleged horse thieves were bound over for trial, and bail was set at several thousand dollars. Since none of the men posted bail, the Butler County citizens held them through Thursday night, December 1, 1870. Near 2:00 a.m. on the morning of Friday, December 2, a crowd of approximately one hundred armed citizens took matters into their own hands. They seized the deputy constable and removed the four prisoners from his guard. They marched the four men a mile and a half south of Douglass to a wooded area where they had constructed a scaffold by placing a board across the branches of two trees. They hung their prisoners by ropes suspended from the board.[7]

By December 2, the vigilante membership had grown to 180, armed citizens. They called themselves “Regulators,” a “vigilance committee.” Since mid-November, the group had drilled in military fashion, preparing for what the local newspapers called “the Butler County War.” When the county officers attempted to arrest the 88 residents involved in the killing of the Booth brothers, Corbin and Smith, the armed vigilantes seized the officers and confined them in the guardhouse. The county attorneys appealed to the governor for assistance, requesting two companies of cavalry soldiers to help re-establish order.[8]

On December 7, Adjutant General David Whittaker and his escort, along with a wagon train of arms and ammunition, arrived in El Dorado, the county seat of Butler County. According to William P. Hackney, the attorney hired to represent the vigilantes, the appearance of the state militia meant the possibility of civil war. With reinforcements from southern Butler and northern Cowley Counties, the vigilance committee organized two battalions of 300 men each and prepared to meet the advancing militia. Another group of 150 slowly advanced north toward El Dorado.[9]

Through skillful negotiation however, Hackney and Adjutant General Whittaker were able to prevent a full-fledged battle from occurring. The 88 vigilantes with outstanding warrants agreed to surrender themselves to the sheriff, and Whittaker agreed to take his supplies and return to Topeka.

The influence of the vigilance committee however, continued to hang over the community. Hackney later reported that the local paper published the vigilantes’ warning: “they had killed four [horse thieves] on November 4th and four on December 4th, and that they proposed to kill four on the 4th of every month thereafter until all were gone, and that any attempt to prosecute them therefore, meant death.” It was signed “798 Vigilantes.”[10] This warning apparently had the desired effect since the charges were dropped against 85 of the vigilantes. The following April, when the cases against the remaining three came to trial, the courtroom was packed with members of the vigilance committee. The judge dismissed the cases and discharged the defendants.[11] The Butler County War had finally ended leaving a plethora of questions unanswered.

In contemporary discussions of the episode, the participants cited the inability of local law enforcement to handle the horse thieves as the reason for the vigilante actions. The purpose of the self-styled “798 Vigilantes,” according to the Central Kansas Index, the newspaper in neighboring Chase County, was to “wipe out at once and forever the gang of outlaws on whom justice had never inflicted a blow, and who were emboldened in their increasing villainies by the inability of the law to arrest them.”[12] The Walnut Valley Times (Times), published in El Dorado, reported that horse theft had been rampant during 1870, and claimed that the formal legal system had proved ineffective. “Public feeling was aroused,” the editors maintained, “and it was evident that some one had to suffer death.”[13] As early as April 1870, the Times reported, “Numbers of horses are missing. Lynch Law should be put in force.”[14]

Why did they feel justified in going outside the law to execute these alleged criminals? Who were the victims of the vigilantes, and for what were they really being punished? Who were the “798” and what was really behind the “Butler County War”? What became of the participants, and how did the community survive such a violent episode?

The search for answers to these questions leads first to a review of the historiography of western vigilante activity. The first section of Chapter Two establishes definitions for the relevant terminology and reviews the historical approach that emphasizes the lawlessness of border communities like that of Douglass, Kansas in the late 1860s and early 1870s. This approach suggests that the perception of inadequate or corrupt law enforcement came together with the ideology of popular sovereignty to justify extralegal violence to control criminal activity. Expanding the categories of analysis to focus more directly on issues of economic and social class, gender, and ethnicity is also a constructive method, but again, a number of questions are left unanswered. Examining the impact of post-Civil War industrialization and economic modernization, for example, while highlighting possible motives of those who might have benefited from the lynchings, does not completely explain this vigilante episode. Early twentieth century western history interpretations asserted that nascent communities in these counties were struggling to establish effective police forces and legal systems, and that vigilantism was a reaction to nonexistent or ineffectual law enforcement. This is not, however, entirely supported by the evidence in this case. As useful as this approach is, it is nevertheless, too narrow to fully explain the events in south-central Kansas.

The key to understanding episodes of vigilantism, lies in determining the motives of the vigilantes, the actions of their targets, and most importantly, the dominant norms and values of their community. To make sense of all this, it is necessary to search for a more comprehensive interpretative framework. Section two of Chapter Two examines a number of theories associated with collective behavior, social deviance and social performance, which offer useful methods for understanding the Butler County events. This cross-pollination of theoretical frameworks generated new possibilities for this study. By combining and modifying these various models, a new conceptual paradigm emerged. This approach offers a more comprehensive assessment of the intersection of numerous contributory factors that resulted in the activities of the “798 Vigilantes.” It also provides a method for examining what these events meant to local residents, the manner in which the community survived this phase of its history, and how the residents reconstructed their community identity. This new model is comprised of four components; each examined in a separate chapter.

1) Context and Conduciveness. Chapter Three explores the background of these events, including an overview of the history of Kansas, Butler County, and the community surrounding Douglass. It examines the stresses and strains on this region, focusing specifically on political issues, post-Civil War animosities, the pressures of large numbers of new arrivals, and criminal activity. It probes the historical foundations and legal traditions that led to the sanctioning of extra-legal action. To assess the existence and efficacy of the legal system, this chapter also includes a review of the organization of laws, the court system and law enforcement bodies in the region.

2) Mobilization. Chapter Four examines the problem of horse theft and the manner in which it was reported in the press in the months and weeks leading up to the November lynching. This includes the ways in which community leaders, particularly the media, helped to shape the discourse surrounding the events and the selection of a scapegoat or deviant group on whom they attached responsibility for the problem. This includes an examination of the specific events that served to confirm or validate their selection of a target. This chapter probes the backgrounds of the vigilantes, the legal authorities, and that of the victims of the first lynching.

3) Action and Reaction. Chapter Five addresses the measures taken by the vigilantes and the proportionality of their response to the behavior of the alleged thieves. It includes an examination of the various accounts describing the two lynching events, as well as the references to the physical evidence associated with the crime scenes. After the vigilance committee’s actions in November, four community members voiced their dissent and took steps to hold the vigilantes accountable. This chapter examines the vigilantes’ reaction to this dissent, by examining the background of the second group of victims, in addition to the vigilantes’ preparation and rationalization of the December lynching. This chapter describes the efforts of the local law enforcement authorities and the state militia to address the problem, and discusses the subsequent trial of three of the vigilantes.

4) Evaluation. The final chapter evaluates the residents’ perceptions of the vigilante episode that enabled them to reconstruct their community following this breach. This involves an examination of how the community made sense of the episode. In the years following 1870, the myth of peace and tranquility provided by the vigilantes for the community was continually belied by repeated reports of horse theft and subsequent demands for vigilante action – yet the myth endured. There is still considerable resistance on the part of many area residents to avoid examining these events in a manner that might confront and disprove the accepted interpretation.

The purpose of this project is to explore in greater detail the events of the fall and winter of 1870-1871 in Butler County, Kansas. According to the research of historian Richard Maxwell Brown, in his classic 1975 study of American violence and vigilantism, the “798 Vigilantes” of Butler County, Kansas, 1870-71, ranks as the eighth-largest vigilante movement overall in American history, and the third-largest in the American west from 1767 through 1904.[15] In the Western states, only the 1856 San Francisco vigilance committee with 6,000 to 8,000 members, and the 1865 Idaho City vigilance committee with 900 members were larger. An examination of the total number of vigilante movements per state reveals that Kansas, with 19 vigilante movements, ranks fourth overall, and third among Western states behind Texas, with 52 movements, and California with 43 movements.[16] The incidents in Texas, California, and Idaho, along with southern lynching in general have received extensive scholarly attention. The Kansas vigilantes have been relatively ignored. These figures indicate that Kansas is indeed an appropriate setting for an examination of vigilantism, and the Butler County “798 Vigilantes,” is an important group.

By constructing a new interpretative framework rather than relying solely upon existing interpretations of western violence and vigilantism, this study proposes a new approach for analyzing such episodes. This approach allows for an examination of the historical foundations and legal traditions that led to this type of violence. This model provides a framework for an examination of the intersection or convergence of contributory factors, and the role of community leaders in shaping the residents’ demand for a collective response to the perceived threat to the social order. It suggests a method for examining the proportionality of their response and the symbolic meaning of their actions, addressing possible triggering events and rituals of punishment. Finally, this new model includes an examination of the events on the identity of the community from the time the events occurred through the most recent assessments of this part of their community’s history.

[1]Daily State Record, Topeka, Kansas, 16 December 1870.

[2] Daily State Record, Topeka, Kansas, 16 December 1870.

[3] Emporia News, Emporia, Kansas, 18 November 1870.

[4] Based on the reports in Wichita Vidette, Wichita, Kansas, 10 November 1870; Walnut Valley Times, El Dorado, Kansas, 11 November 1870; Emporia News, Emporia, Kansas 16 December 1870; and the Daily Kansas State Record, Topeka, Kansas, 16 December 1870. The accounts vary slightly. I have given preference to the State Record account, which appears to be the most comprehensive.

[5]Jessie Perry Stratford, Butler County’s Eighty Years, 1855-1935: A History of Butler County, Biographical Sketches and Portraits. El Dorado, Kansas: Butler County News, 1934.

[6] Wichita Vidette, Wichita, Kansas, 8 December 1870.

[7] Based on the reports in Wichita Vidette, Wichita, Kansas, 8 December 1870; Walnut Valley Times, El Dorado, Kansas, 9 September, and 9 December 1870; Republican Journal, Lawrence, Kansas, 7 December 1870; Emporia News, Emporia, Kansas, 9 December 1870.

[8]E.L. Akin, letter to Governor James M. Harvey, 2 December 1870; W.H. Redden letter to Governor James M. Harvey, 2 December 1870, Governor’s Correspondence for 1870, Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas.

[9] William Patrick Hackney, “The Butler County War,” in Volney P. Mooney, History of Butler County Kansas (Lawrence, KS: Standard Publishing: 1916), 257.

[10] Hackney, “The Butler County War,” in Mooney, History of Butler County, 258.

[11]Hackney, “The Butler County War,” in Mooney, History of Butler County, 260.

[12] Central Kansas Index, Chase County, Kansas, 28 December 1870.

[13] “The Butler County War,” Walnut Valley Times, December 1870.

[14] Walnut Valley Times, 29 April 1870.

[15] Richard Maxwell Brown, Strain of Violence: Historical Studies of American Violence and Vigilantism, (NY: Oxford University Press, 1975), 305-319. The issue of defining the physical location of the region referred to as “the west” is problematic at best. For the purposes of this project, I am utilizing the seventeen core states of Patricia Nelson Limerick’s list: California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas, Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota and South Dakota. I am excluding the continuation of her list “more changeably, Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, and Louisiana.” Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West, (NY: W.W. Norton, 1987), 26.

[16] See Appendix 3 in Brown, Strain of Violence 305-319. A third possibility, the 1859-1861 Denver vigilantes were perhaps equal in size to the Butler County vigilantes. I have not included them above because there is some question as to their actual size. Brown’s chart states the number of movement members of this group was somewhere between 600 and 800. Butler County vigilantes were the third largest group of vigilantes among movements in the west. Only the 1856 San Francisco vigilance committee with 6,000 to 8,000 members, and the 1865 Idaho City vigilance committee with 900 members were larger.[16]