That chance of fate occurred during final training in Oklahoma where the commander of Jack's 34th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron and the commander of the 32nd Photo Recon Squadron had the option of going to either England or Italy. Jack's CO won the toss and chose England.

Except for the pilots who were flown to Italy, the rest of the 32nd squadron, numbering more than 300, were lost when their ship was sunk in the Mediterranean.

One of four photo recon squadrons planned for overseas duty, the 34th

became operational on Dec. 15, 1943, at Will Rogers Field in Oklahoma City.

A fifth, the 35th squadron, was later organized and sent to the China-Burma-India

theater.

One of four photo recon squadrons planned for overseas duty, the 34th

became operational on Dec. 15, 1943, at Will Rogers Field in Oklahoma City.

A fifth, the 35th squadron, was later organized and sent to the China-Burma-India

theater.

On March 21, 1944, the 350 men in Jack's squadron joined some 17,000 other servicemen aboard the Queen Mary, the sleek British "Pride of the Seas" converted into a troopship, at New York City and sailed unescorted across the Atlantic.

Jack recalled, "We were five decks below the main deck. The ship was too fast for escorts to keep up and to be threatened by German subs. Normally, she could cross the Atlantic in three days but it took four days with zigzagging."

Anchoring in Scotland's Firth of Clyde, the troopship disgorged its human cargo into barges for the trip to shore. From there, the members of the 34th went by train from Glasgow to Oxford, England, some 50 miles west of London. Oxford would be the squadron's base for five months. The unit arrived in Oxford on March 29 and with around-the-clock preparations became operational on April 19. Oxford was originally intended as an RAF bomber base but was turned over to the Americans because of the need for aerial reconnaissance.

The squadron's history states:

"Our flying tactics were fairly consistent with those handed down by

our sister photo pilots from the 8th Air Force and the early Spitfire photo

expertise adapted by the RAF. They were premised upon three principles:

first, get the pix home; secondly, in order to accomplish this, fly above

the 'ack-ack' (anti-aircraft fire), normally about 30,000 feet; and thirdly,

whenever possible, stay above or below the contrail level to help avoid

being spotted by the enemy ... the photo 'recce' mission was not a success

until the 'product' was returned home and properly processed. Coldly and

statistically speaking, the bomber pilot was successful as long as he laid

his 'eggs' on his target, even if he didn't return. And as long as the fighter

boys safely escorted the 'big babies' to their destination they were at

least partially successful. But not so with the photo pilot.

The squadron's history states:

"Our flying tactics were fairly consistent with those handed down by

our sister photo pilots from the 8th Air Force and the early Spitfire photo

expertise adapted by the RAF. They were premised upon three principles:

first, get the pix home; secondly, in order to accomplish this, fly above

the 'ack-ack' (anti-aircraft fire), normally about 30,000 feet; and thirdly,

whenever possible, stay above or below the contrail level to help avoid

being spotted by the enemy ... the photo 'recce' mission was not a success

until the 'product' was returned home and properly processed. Coldly and

statistically speaking, the bomber pilot was successful as long as he laid

his 'eggs' on his target, even if he didn't return. And as long as the fighter

boys safely escorted the 'big babies' to their destination they were at

least partially successful. But not so with the photo pilot.

"The first major job facing the 34th was to provide beach photography in the Normandy area to give planners a first-hand picture of what would be facing the invasion armada on D-Day. But the extent of the photography was expanded to include the southern Belgian coast and the entire French coast south to Cherbourg to help lessen the chances of the Germans possibly pinpointing an exact invasion location.

"To enhance the element of surprise," the history continues, "all missions would be flown just above water level from the British coast to target area, hence aircraft would be safely below all enemy radar surveillance and subject to minimum detection. The tradeoff achieved from cloudless conditions would more than make up for the amount of distortion which would be experienced from the oblique photography taken at such extreme low altitudes and speeds of 300-plus mph. Each plane was retrofitted with the installation of right and left side-looking oblique cameras equipped to run continuously with the nose camera, also installed in the oblique position. All missions were flown during time of low tide in order to photograph all underwater obstacles and consequently maximize overall beach photo coverage. Most of these missions were flown between May 6 and 20, 1944. D-Day was June 6."

The history continues: "Lt.

Keith (1st Lt. A.R.) drew the very heavily defended coastline of LeHarve

and vicinity. Small arms and coastal defenses caused him little or no trouble,

but a seagull smashed into his canopy. Keeping his aircraft under control

while covered with blood and feathers proved no easy task and left little

margin of error at this (low) altitude. Nevertheless, he managed to bring

both 'birds' as well as excellent photography home."

The history continues: "Lt.

Keith (1st Lt. A.R.) drew the very heavily defended coastline of LeHarve

and vicinity. Small arms and coastal defenses caused him little or no trouble,

but a seagull smashed into his canopy. Keeping his aircraft under control

while covered with blood and feathers proved no easy task and left little

margin of error at this (low) altitude. Nevertheless, he managed to bring

both 'birds' as well as excellent photography home."

To 2nd Lt. G.A.York, the youngest of the original pilots in the squadron, went the plaudits of all. As the D-Day invasion unfolded, it became common knowledge that he had photographed the exact location of the Normandy beaches that the American forces landed on. He had photographed all of Omaha and most of Utah beaches. Like similar low-level missions flown up and down the coast, Garland had pinpointed the beach barriers, teller mines attached to imbedded posts under water during high-water conditions and other coastal defenses in minute detail as well as scattering his share of German soldiers working along the beaches.

In the Presidential Unit Citation and other commendations received by the squadron, it was stressed that the information provided by these aerial photographers saved countless allied ground and naval invasion personnel.

And due credit is also given the marvelous twin-engine, twin-boom P-38. The history states: "For our purpose, in its day, it met our every requirement. Even at the extreme altitudes when cracked magnetos and associated engine failure sometimes seemed more than common, we always had that second engine to bring us home. Our F-5s (a P-38 model) under all conditions really 'brought home the bacon.'"

Jack explained that as soon as an aircraft returned from a mission, it would park for refueling. The film was removed from the cameras and new film installed. (It took less than an hour to develop the film and process prints.) At the same time, Jack and the other flight-line men would check with the pilot for anything needing immediate attention and then give the plane a thorough checkover. "We'd first wash off all the oil" covering much of the aircraft, Jack explained, because the P-38 was notorious for "throwing oil." But that did not affect its performance.

There was a darker side, too. Although no pilots were lost to enemy action, the 34th lost four of its original 18 pilots, while based in England, to anoxia (oxygen deprivation) while flying high altitudes; another pilot was declared missing and three others died in accidents in Europe.

After five months in England and as allied forces swept deep into France, the 34th moved to an airfield on the Brest peninsula, and it hopscotched four more times to keep up with the rapidly advancing forces. In one day, the 34th lofted 29 missions mapping 10,000 square miles and delivered 200,000 photographic prints to the 3rd Army.

On its fifth move across France, to near Nancy on the Mozelle River, the 34th was faced with a predicament. Its sod field, subjected to heavy rain and then snow and freezing, was sinking, despite much fill which was trucked in. "Just in time," the history reports, "the Engineers thundered in. God bless 'em. The battalion was an all-black unit, every man from the South. Down to the last man they knew their job and they really did it. Theirs was a tremendous effort, an engineering miracle."

Jack vividly recalled the unit's first night there. After setting up camp and with the poles for the six-man tents pounded into the soft ground, the unit bedded down for the night. Suddenly, nearby tank and artillery units from Gen. Patton's 3rd Army let loose with a terrific barrage. "The concussion blew down every single tent, except the mess tent which was on a wooden frame," said Jack.

In November and December of 1944, during a period which the history calls a "living hell," Jack was among the ground crews "working their heads off to keep 'em flying. When not in mud up to their ears, the workers on the line were literally freezing. Workers' hands actually stuck to cold metal. When conditions were at their worst, our men had to relieve one another every 15 or 20 minutes in order to keep from freezing fingers." (It was during that period of bad weather, from Dec. 17 to the 23rd, that the Germans launched their last desperate offensive in Belgium, just 30 miles north of the 34th's field, which became known as the Battle of the Bulge.)

Photos taken in 95 missions and 158 sorties by the 34th and its sister units paved the way for the subsequent breakthrough of the German Siegfried Line defenses by the Seventh Army.

"For the first time," the squadron history continues, "things were beginning to loosen up," with three-day passes to Paris, seven-day furloughs to England and extended visits to the French Alps and French Riviera.

The "great day" arrived on May 8, 1945, with the surrender of the German forces in Europe. "To a man, the squadron accepted V-E Day quite calmly. There was little or no jubilance displayed. Each preferred to go in his own direction and reflect in his own way."

But it wasn't quite over for the 34th Photo Reconnaissance Squadron. In its last operations in Europe, it collected heretofore unavailable European photography, much of it in the western (later to be called) "Iron Curtain" countries. Priority photographs of command, control and communications centers, in particular, would remain in demand by the U.S. intelligence community for years to come. During those sorties, anti-aircraft fire "by our supposed allies" was common.

For the last four months of its tour, the squadron was assigned to Furth/Nuremberg, "a country club" compared to all its previous homes. Jack was discharged Nov. 17, 1945, at Fort Smith, Ark., and the squadron was deactivated on Nov. 22.

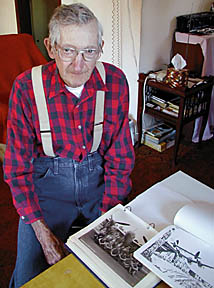

Jack, who turned 80 in August, was born in Augusta's Foxbush oil field where his father, Eddie Howe, was a roustabout. His mother was the former Faye Rausch. Jack was 11 when his father died and he was "farmed out" in western Kansas. He finished the eighth grade there.

He was drafted into the Army in early 1943 while working in the Boeing machine shop on the PT trainer landing gear. "I could've stayed home because I was supporting my mother and three sisters, and Boeing had given me a good offer." Before going overseas, he married Cynthia Cain of Wellington on Nov. 6, 1943.

"After basic in St. Petersburg, Fla.," Jack said, "40 of us were sent to the New England Aircraft School in Boston for our A&E (aircraft mechanic) license. Then to P-39 school at the Army Air Corps Technical Training Command at Camp Bell, N.Y., outside of Buffalo. I was one of 11 in that class. We checked out as mechanics on the P-39 - that's the one with the 37 mm cannon in the nose. We completed that course in the summer of 1944 and were sent to Savannah, Ga., where it was 110 in the shade."

"My wife was a riveter at Boeing, and they laid her off when I went back there" after his November 1945 discharge. On returning to Boeing, he worked on final assembly of the B-47 bomber.

After about a year there, he worked as an auto mechanic for a succession of garages, including Jack Lane Chevrolet in Wellington, Hugh Elam Motor Co., "the Dodge dealer" in Winfield, Wes Drennan Pontiac and then six years with Butler Bros. servicing the company's trucks. In 1966, he went to work at General Electric's Aircraft Engine Maintenance Center at Strother Field, mainly in the accessories department and later in the test cell. He retired from GE in 1985.

A few years before he retired, he and his wife built their house south of Winfield on what was once known as Cemetery Road, now 81st. "We ordered it from a Sears catalog," Jack explained, "and we've never been sorry." The four-bedroom dwelling sits on five acres, much of which is taken up by the fruit orchard - apples, pears and peaches - which they first set out, and a large vegetable garden.

"We raise more sweet potatoes than anything else," commented Cynthia.

"It keeps us busy," said Jack.

They are members of First Baptist Church of Winfield, and Jack is a member of the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars. He is a 32-year member of the National Rifle Association. All the packages of venison steaks and sausage in their freezer attest to his prowess as a hunter.

The Howes have three children: Eddie Lee of Wilmer, Minn., Donna Fay Isbell of Underhill, Wis., and David L. Howe of Winfield. They also have four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

(Column note: Most of the background material for this article came from the squadron's "Reflections," a collection of recollections of the unit's active-duty period from 1943 to 1945.)